Recording a Deed? The Unsexy Little Step That Actually Makes You the Owner

You know that feeling right after closing? You’ve got keys, you’ve got a stack of papers thick enough to stop a door from slamming, and you’re already mentally placing your sofa in the living room like a Sims character.

And then someone says, “Make sure the deed gets recorded.”

Cue the blank stare.

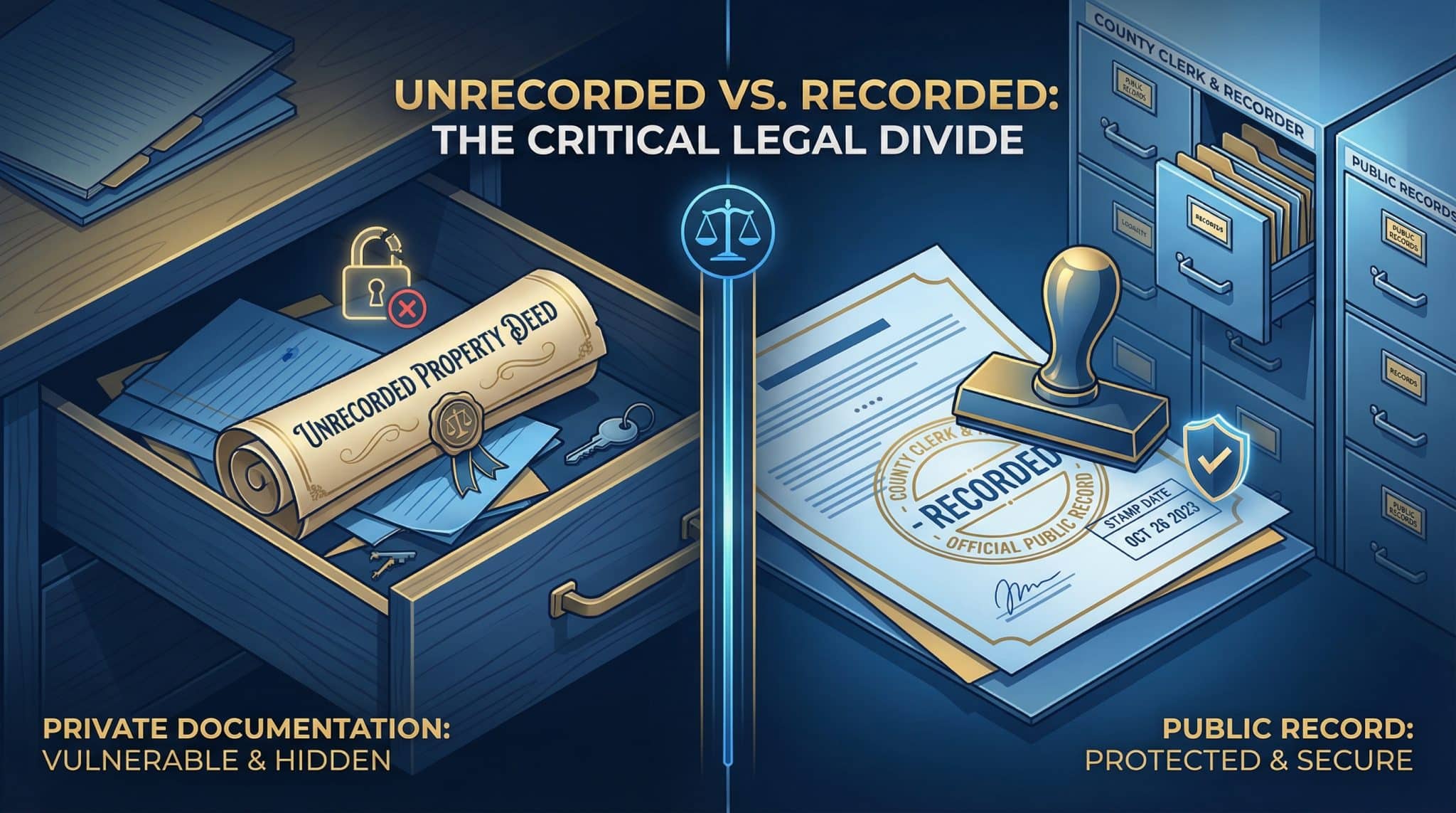

Here’s the deal (pun absolutely intended): until your deed is recorded in the county’s public records, your ownership is basically not “official official.” And in some states, recording first can matter if there’s ever a dispute meaning the person who records first can have priority. Which is a terrifying sentence to read after you’ve just wired your life savings.

So let’s make this simple, so you can get it done right the first time and go back to arguing with yourself about paint colors like a normal homeowner.

First: What “recording” actually is (and why you should care)

Recording a deed = filing the signed deed with the county recorder (sometimes called the county clerk or registrar recorder) so it becomes part of public record.

Once it’s recorded, it creates what’s called constructive notice, which is fancy legal speak for: “Everyone is treated like they know you own this place now.”

If the deed never gets recorded (or gets rejected and no one fixes it), you can end up with:

- delayed ownership protection

- annoying problems later when you refinance/sell

- the kind of paperwork spiral that makes you want to move into a yurt

Yes, it’s boring. Yes, it matters.

“How much does it cost?” (Recording fees vs. the other money monster)

Most people hear “recording fee” and assume it’s like… $20 and a smile.

In reality, recording fees are usually somewhere around $25 to $125 for a basic deed, but they vary a lot by state and sometimes by county.

The two big ways counties charge

- Flat fee states: predictable, bless them. (Example: some states are around $25-$30.)

- Per page states: the longer your document, the more you pay. A deed that’s cheap in one state can cost noticeably more somewhere else just because it’s a few pages longer.

The “wait, why is this so high?” states

Some places stack fees and surcharges in a way that feels like ordering a $9 latte and getting a $22 receipt.

- California can add fees that bring a basic recording to something like “almost $100” in certain counties.

- New York can land in the $190-$265-ish neighborhood once you’re done complying with the required filings.

Sneaky little add-ons that surprise people

Not everywhere does these, but they pop up often enough that I have to warn you:

- Indexing/name fees if there are “too many” names to index (trusts and LLC situations can trigger this fast)

- County specific surcharges that don’t show up in basic state summaries

- Multiple document charges if what you think is “one thing” is treated as two or three documents by the recorder

If you want the least stressful plan: check your county recorder’s fee schedule (not just a random internet list), and assume it’ll be slightly more annoying than you hoped.

Important: transfer taxes are NOT the recording fee

Recording fees pay the county to process/store the document.

Transfer taxes are a separate beast and are usually based on sale price meaning they can dwarf the recording fee. Like, “you’ll remember it forever” dwarf it.

So when someone tells you, “Recording is cheap,” they might be right… and you still might be paying transfer taxes that are very much not cheap.

The #1 reason deeds get delayed: rejection for formatting (yes, really)

County recorders aren’t judging your design skills or deed layout basics. They’re judging whether your document can be scanned, indexed, and stored long term without chaos.

And they will reject it for stuff that feels petty until you’re the one re-mailing a packet for the third time.

Here are the biggest “don’t get kicked back” rules that come up over and over:

The basics that save you

- Paper size: usually 8.5″ x 11″ (some counties allow legal size, but don’t guess)

- Margins: leave generous margins especially at the top

- That blank box on page one: many counties want a blank area in the top right of the first page for their recording stamp (often described as about 3″ x 5″). Don’t put text there because you got ambitious with spacing.

- Ink: black or dark blue. Avoid red ink like it’s cursed.

- Legibility: light printing and smeared seals can get rejected

Content that’s commonly required (aka the missing info hall of shame)

Every deed should clearly include:

- grantor (seller) and grantee (buyer) names

- a mailing address (often for tax statements and official notices)

- the legal description of the property (not just the street address)

- often the APN/parcel number as supplemental ID

- preparer info (who prepared the document)

- a return address (where they send the recorded deed)

And yes, some counties get spicy about what must appear on the first page. Use your county’s checklist like it’s the last life raft on the Titanic.

Signatures and notarization: don’t DIY this part with vibes

- Original signatures are typically required (not photocopies)

- Names should match consistently across the deed and notary block

- Notary seal needs to be clear and scannable (no faint, half moon stamp that looks like a ghost tried to notarize it)

Witnesses: depends on your state

Some states require witnesses in addition to notarization (Florida is a common example). Others don’t. This is one of those “don’t take advice from your cousin’s closing in a different state” situations.

“Do I need extra forms?” Maybe. Don’t panic.

A lot of people need zero supplemental forms. Some need one. A few states love paperwork the way I love a good before and after photo (too much).

Examples you might run into:

- California: a Preliminary Change of Ownership Report is commonly required with the deed (skip it and you can get a penalty).

- New York: transfer forms like TP-584 and RP-5217 are typically part of the party, and requirements can be very specific.

- Cook County, Illinois: a transfer tax declaration (MyDec) is done online before the recorder will accept the deed.

The key is this: don’t try to memorize “what New York does” if you’re recording in Arizona. Go straight to your county recorder’s site and pull their current checklist and current form versions.

Outdated forms are a classic rejection trigger. (Ask me how I know actually don’t, it still hurts.)

Paying the fee without creating a new problem

In person, most offices accept some combo of cash, card, money order, cashier’s check, and sometimes personal check.

A few practical notes:

- Cards may come with a processing fee (often around ~3%).

- If you’re paying by check, make it payable to the exact office name listed on the recorder’s website. Close doesn’t count here.

- If you’re mailing it, don’t underpay. Underpaying usually = rejection. Overpaying can mean delays while they process a refund.

How to submit your deed (pick your adventure)

You file with the county where the property is located not where you live now, not where your mailing address is, not where your mother insists the “main courthouse” is.

Typically you’ve got three options:

1) In person (fastest + least mysterious)

If you can go in person, you’ll often find out immediately if something is wrong. Sometimes you can fix small issues on the spot, which feels like winning the lottery but with fluorescent lighting.

2) By mail (fine, but slower and riskier)

Mail adds transit time both ways if anything gets rejected. If you mail:

- use trackable shipping

- include a return envelope

- triple check fees and forms

3) E-recording (very fast, but vendor based)

Some counties allow e-recording through approved vendors. It can be super quick sometimes same day or within 24 hours but only if you use the correct channel and format.

Check the county recorder site for the approved vendor list. If you send it the wrong way, they’ll reject it with the emotional warmth of a parking ticket.

How long does recording take? (And why you shouldn’t obsess over the mail)

Timing varies, but generally:

- In person: often recorded the same day if you make the cutoff time (commonly mid afternoon)

- E-recording: often within 24 hours

- Mail: often a few business days after they receive it

After it’s “recorded,” it may still take extra time for scanning/indexing to fully show up in searches.

And getting your stamped original back in the mail? Commonly 10-14 business days, sometimes longer.

Important nuance: the recording date is what matters legally, not when the stamped copy shows up in your mailbox.

Want proof fast? Ask for a conformed copy.

If you’re the type who sleeps better with receipts (hi, it’s me), ask for a conformed copy when you record basically a copy stamped with recording information. It’s often just a few bucks.

A certified copy is more “official” and usually only needed for certain legal/court situations for getting an official deed copy. Most homeowners don’t need that immediately.

“Wait… isn’t my title company handling this?”

Often, yes. In a standard purchase, the title company or closing attorney typically records the deed as part of closing.

But here’s my very opinionated homeowner advice:

Don’t assume. Verify.

I’ve seen people discover months later that something got rejected, then the paperwork got buried under other paperwork, and now everyone’s pointing fingers like it’s a group project in high school.

So even if a pro is handling it:

- ask when it was submitted

- ask for the recording info (instrument number / recording number)

- save your closing packet like it’s a family heirloom

Tiny tax note (not sexy, but useful)

Recording fees generally aren’t an itemized deduction. But they often add to your cost basis, which can matter when you sell.

It’s not usually a huge dollar for dollar game changer, but it’s worth keeping your Closing Disclosure and final paperwork so your future self isn’t trying to reconstruct costs from a shoebox of receipts.

When to call in a pro (because sometimes “DIY” is a trap)

If this is a straightforward purchase and your closing team is on it, you’re probably fine.

But I’d seriously consider a real estate attorney or title professional if:

- the property is going into a trust or LLC

- you’re trying to fix or correct an already recorded deed

- there are title issues, family transfers, divorces, inheritances, weird boundary stuff, etc.

- your county’s requirements read like they were written by someone who hates joy

Also: the recorder’s office is not your legal safety net. They’re checking format and basic requirements not confirming the transfer is legally perfect.

My “don’t get rejected” mini checklist (print this, save it, tattoo it kidding)

Before you submit, confirm:

- You’re filing in the correct county

- You used the county’s current required forms (if any)

- The first page leaves space for the recorder’s stamp

- All required names/addresses/legal description are included

- Signatures are original, names match, and notarization is clean

- Payment is correct and payable to the right office name

- Return address is on the document (or clearly included)

Do that, and recording stops being this ominous mystery and becomes what it should’ve been all along: a mildly annoying errand that you finish once.

Now go enjoy your house. And if you’re not enjoying it yet because it smells like the previous owner’s candle collection… congratulations, you’re officially one of us.