Why Your Unrecorded Deed Could Cost You Everything (Yep, Really)

If you just felt a tiny spike of anxiety because you think your deed is sitting in a folder somewhere (possibly under takeout menus and that one mysterious Allen key), hi. You’re my people.

Here’s the not fun truth: a deed that’s signed but not recorded can leave you weirdly exposed, even if you paid for the property fair and square. It’s one of those grown up paperwork things that feels boring right up until it’s… not.

I’m going to walk you through what “recording” actually does, what to check, and what to do if you just discovered an unrecorded deed from three years ago (or, like, 1997).

(Quick note: I’m not your attorney. I’m just the person shaking you gently by the shoulders telling you to go check your county records.)

The 10-minute version: what you should do today

Pick the scenario that sounds like your life:

1) You just closed / just signed

Record it immediately (same day is ideal). Then verify it shows up in county records with the correct names.

2) You think it was recorded

Don’t guess. Look it up on your county recorder’s site using your name and/or the property address. Find the instrument/document number and recording date.

3) You found an old deed that was never recorded

Don’t panic. Do act. Generally: record it, then run a title search to see what happened while it was floating around unrecorded. If you see anything fishy (another deed, lien mess, probate drama), stop and call a real estate attorney.

If you do nothing else after reading this post: go check your county recorder website. Right now. I’ll wait.

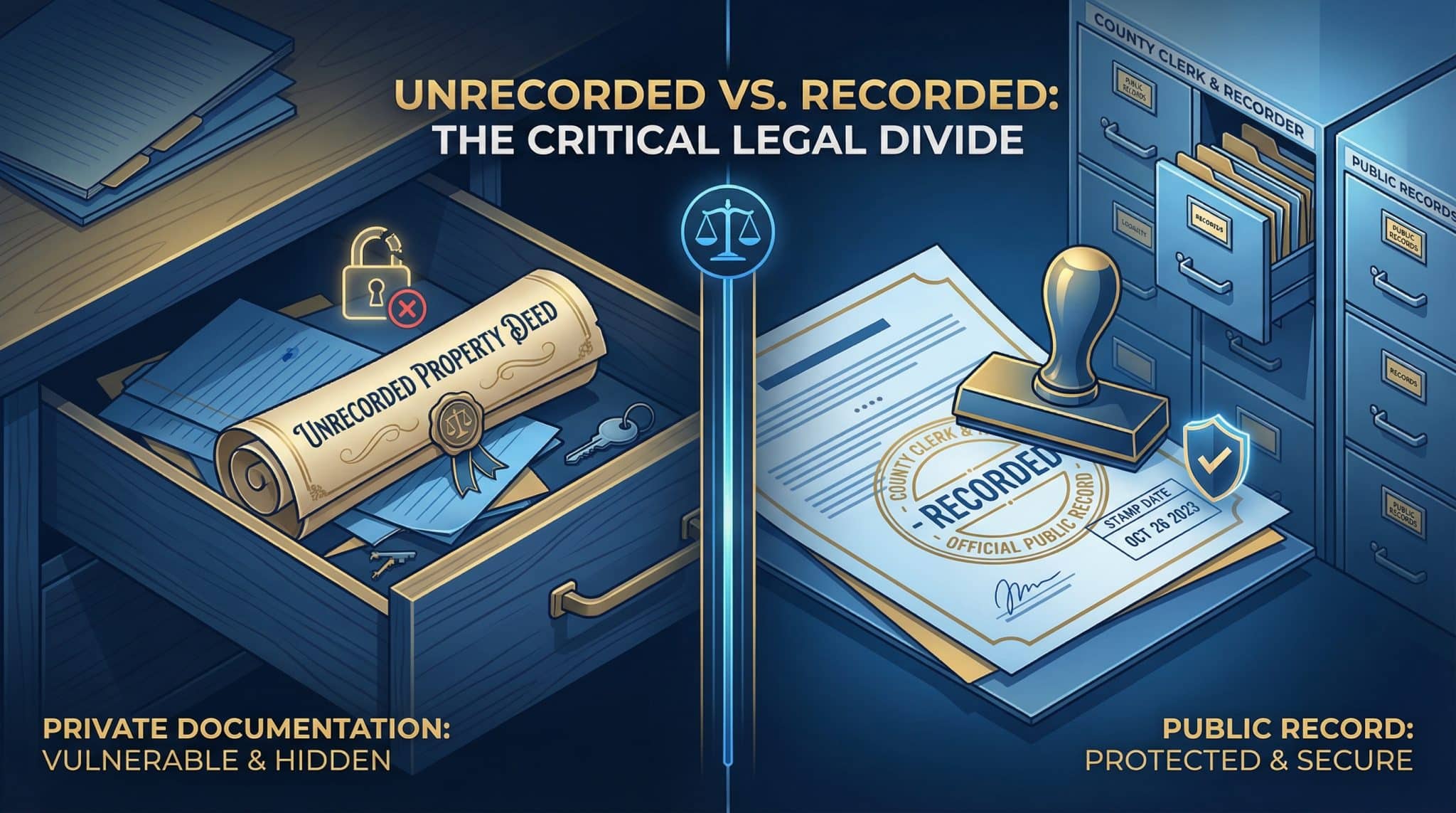

“But I have the deed.” Cool. That’s not the same as being protected.

This is the part that makes people mad (understandably):

A signed deed in your drawer can be valid between you and the seller. Like: “we shook hands, we did the thing, the property transferred.”

But if you don’t record it, the rest of the world is basically allowed to act like the public record is the truth.

Recording is what turns your private transaction into a public one.

I explain it like this:

- Signing the deed = the handshake

- Recording the deed = the megaphone

Without the megaphone, a later buyer, lender, or creditor can come along and say, “Well, I didn’t know about your handshake,” and depending on your state laws, that can get ugly fast.

What recording actually does (in plain English)

When you record your deed with the county:

- It creates “constructive notice.”

Meaning the law treats it like the public “knows” your deed exists because it’s in the public record—even if nobody bothered to look. - It protects your “priority.”

In a lot of disputes, the recording date is what decides who wins. - It keeps your chain of title clean.

This is the recorded history lenders and title companies want to see when you refinance or sell. No recording = chain breaks = everyone gets cranky.

And by “everyone,” I mean lenders, buyers, title companies, and occasionally judges. So… not the fun kind of cranky.

Why timing matters (and why waiting is basically inviting chaos)

States have different rules for what happens when two people claim rights to the same property. The names vary, but here’s the gist:

- Some states are basically “first to record wins” (even if they knew about an earlier unrecorded deed).

- Some protect a later buyer who didn’t know about your unrecorded deed.

- A lot of states are a combo: later buyer wins only if they didn’t know and they recorded first.

Translation: every day your deed isn’t recorded is a day you’re needlessly playing defense.

Recording right away isn’t paranoia. It’s seatbelt energy.

How to record your deed without getting rejected (aka: avoid the “nope” pile)

Counties can be picky. And unfortunately, the recorder’s office is not your personal proofreader.

Generally, make sure your deed has key deed sections:

- Correct grantor and grantee names (and usually addresses)

- A complete legal description (not just the street address)

- Proper signatures

- A notary acknowledgment that’s actually done correctly (legible seal, notary name, expiration, etc.)

- Any required margins/formatting

- The right recording fee

And yes, rules vary a lot by location. Some places have specific page sizes, witness requirements, blank margin space requirements, or penalties if you record late. So before you print anything, check your county recorder’s requirements.

Filing options, ranked by “how much I trust it”

- In person (best if you can): you can fix issues on the spot and often get confirmation immediately.

- E-recording (great if available): usually fast—often within a couple business days.

- Mail (least comforting): slower and if it’s rejected, you find out later… after you’ve been casually vulnerable for weeks.

Don’t do a victory lap until you verify it’s indexed correctly

Here’s a sneaky thing people don’t realize: sometimes a deed can get recorded, get a number, and still not protect you the way you think if it’s mis-indexed or missing in the way it’s supposed to show up.

And the recorder’s office isn’t going to call you like, “Hey bestie, just letting you know your deed is basically invisible.”

What I’d do:

About 5-10 days after recording, look it up and make sure it appears correctly under:

- the grantor (seller) name

- the grantee (you) name

- and/or the property address/parceled ID, depending on how your county searches work

If it’s missing, unfindable, or clearly wrong: treat it as urgent.

If your deed is old or has errors: how fixes usually work

Public land records don’t get “edited.” They get added to. So fixes often mean recording another document that corrects the first one.

Common paths (and this is where you may want professional help):

- Corrective deed: for big problems (wrong legal description, wrong name, missing parcel, etc.). Often needs the original grantor to sign again, which is… fun if it’s been years.

- Scrivener’s affidavit: sometimes used for smaller clerical errors (like a typo), depending on your area and what your recorder accepts.

- Quiet title action: the legal “let’s settle this” route when things are truly tangled (missing grantor, deceased parties, competing claims, etc.). These can take months and often cost thousands.

If you’re seeing probate issues, bankruptcy issues, fraud concerns, or multiple people claiming rights—please don’t DIY your way through that with vibes and hope. Call a real estate attorney.

The real world cost of delaying (this is the part that stings)

An unrecorded deed can lead to:

- Competing claims (someone else buys it, mortgages it, or records something first)

- Lien and creditor problems tied to the seller (judgments, bankruptcy complications, etc.)

- Refinancing/selling problems because lenders and buyers want a clean recorded chain

- Quiet title lawsuits (often $2,000-$10,000+ and 3-12 months—which is not how anyone wants to spend a year)

I once heard someone describe an unrecorded deed as “owning a house in your heart.” Which is poetic. But lenders and courts are famously not poetry people.

Two recording myths that cause a ton of mess

Myth #1: “I have the deed, so I’m protected.”

You’re protected against the seller in many cases. You are not automatically protected against:

- later buyers

- lenders

- creditors

- anyone relying on public records

Myth #2: “If it’s recorded, it must be legit.”

Recording offices mostly check that your document meets formatting and notary requirements for deeds. They’re not doing a deep truth audit. A forged deed can get recorded. Recording is important, but it isn’t a magical force field.

Which leads us to…

Title searches + title insurance (the boring heroes)

A title search looks back through decades of records for things like:

- liens

- easements

- weird gaps in ownership

- judgments

- missing heirs

- recorded documents that shouldn’t exist but do (love that for us)

Title insurance exists because even good searches can miss hidden issues. There are typically:

- Lender’s policies (usually required if you have a mortgage, protects the lender)

- Owner’s policies (optional in many cases, protects you)

Personally? If you’re able to get an owner’s policy when you buy, I’m a fan. Paying a few hundred bucks once beats paying thousands later because some ancient paperwork gremlin crawled out of the records.

A simple checklist to wrap this up (because you have things to do)

- Search your county recorder’s site for your deed (by name/address).

- Confirm you see a recording date and document/instrument number.

- Make sure it’s indexed under the right names (seller + you).

- If you don’t see it: record it ASAP (in person or e-record if possible).

- If it’s old or you’re unsure what happened in the meantime: get a title search.

- If anything looks complicated or contested: call a real estate attorney before you start filing “fixes.”

Your house shouldn’t be held together by hope, a manila folder, and a prayer. Go make your ownership official public record real.